In an age where our smartphones already track our location, our purchases, and our social circles, the UK government is now proposing to centralise our very identity into a single, state-sanctioned digital credential. The BritCard, touted by ministers as a modern convenience to simplify access to public and private services, is being met with fierce opposition from civil liberties groups who warn it represents the single greatest expansion of state surveillance power in a generation.

Beneath the veneer of bureaucratic efficiency, a storm is brewing over privacy, consent, and the fundamental relationship between the citizen and the state.

What is the BritCard?

In Autumna 2025 the government declared that a new national digital ID scheme would be rolled out to UK citizens and legal residents. The scheme is described as free, stored on people’s smartphones, and will initially be mandatory for right-to-work checks.

According to government material, the digital ID will be held in the GOV.UK Wallet and may later facilitate access to services such as driving licences, childcare, welfare, tax-records, even voting.

Critics point out that while not labelled a physical “ID card”, the functional effect is that many people will need to use the digital ID to obtain work, housing or services, making it compulsory “in all but name”.

A bridge to a two-tier society?

The government’s own announcement frames the BritCard as a voluntary scheme designed to make proving one’s identity “easier and safer.” However, critics argue that the notion of ‘voluntary’ is a slippery slope. As demonstrated in other countries that have adopted digital ID, what begins as an option can quickly become a necessity for accessing essential services like healthcare, benefits, or even commercial activities.

An investigation by The Telegraph highlighted fears that the BritCard could “make Britain’s two-tier society worse,” creating a divide between those who can easily navigate the digital system and those who cannot, such as the elderly, the digitally excluded, the homeless, and others who simply do not want to be tracked by Big Brother.

This is not a theoretical concern. The Open Democracy report draws a direct and chilling parallel to India’s Aadhaar system, where linking the digital ID to everything from bank accounts to food rations led to the “exclusion of an estimated 1.2 million children from a free school meals programme” due to authentication failures. The fear is that Britain is importing a model with a proven track record of harming the most vulnerable.

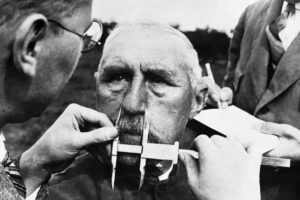

The Surveillance State, Centralised

The most profound alarm bells are ringing over data privacy and state control. By design, a digital ID creates a centralised log of a person’s interactions. Every time you use your BritCard to access a GP, rent a property, buy age-restricted goods, or even use a public library, a transaction is recorded.

The civil liberties group Big Brother Watch has been vocal in its condemnation. In a statement published on its website, it said: “From a privacy perspective, this new proposal is just as dangerous as those that have come before. It would fundamentally change the nature of our relationship with the state and turn Britain into a “papers, please” society, putting the burden on all of us to prove our right to be here.

“It is unclear how such a digital ID would deliver on promises to tackle illegal migration better than existing measures, such as the e-visa scheme, which is riddled with system failures and inaccuracies. But the debate about digital ID isn’t really about immigration; it’s about gaining access to, and control of, everyone’s data.

“Never mind that doing so would trample privacy rights and create huge digital security risks, as well as pave the way for further digital exclusion. But the debate about digital ID isn’t really about immigration; it’s about access to, and control of, everyone’s data.”

This “architecture for a surveillance state” is the core of the dystopian fear. With this infrastructure in place, a future government could easily move from a permissive to a punitive model. The ID could be used to track, score, and control population movement and access to rights.

Imagine a future where your access to a protest, your ability to travel on public transport, or your eligibility for a loan is contingent on a ‘trust score’ linked to your BritCard. This is not science fiction; it is the lived reality in China’s social credit system, and the BritCard provides the technological foundation for a similar model to be replicated in the UK.

Civil liberties organisations point to the inevitable “function creep” that accompanies such schemes. What starts as a way to access a government portal may soon be required to open a bank account, get a SIM card, or verify your age on social media. The identity you use for your taxes becomes the identity you must use for every facet of your life, eroding any last vestiges of anonymity.

A Crossroads for British Liberty

The government insists robust data protection laws will safeguard citizens. However, the UK’s recent track record with large-scale IT projects and the constant threat of sophisticated cyber-attacks make the promise of an unhackable system seem naive at best.

The introduction of the BritCard places the UK at a constitutional crossroads. It forces a national conversation about what kind of country we wish to be: one that prioritises frictionless efficiency and state control, or one that fiercely guards the privacy, anonymity, and fundamental liberties that have long been its hallmark.

The debate is no longer about a simple digital card. It is about the power to define who we are in the eyes of the state, and how much of our lives we are willing to hand over for the sake of convenience. As the rollout begins, the question for every Briton is: at what cost?

Follow Us!